Dr. Aduragbemi Banke-ThomasAXA Research Fund Fellow

September 6, 2021

How Google Maps Can Help with Efforts to Tackle Delays in Accessing Critical Maternal Health Services

3 minutes

Original content: AXA Research Fund in partnership with The Conversation

Every year, 295,000 women die from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth globally. Nigeria accounts for an enormous 23% of these deaths. Each one is a needless tragedy, and preventing them should be a global priority.

How can we do so? Research has shown that prompt access to nine critical maternity services, together known as emergency obstetric care, can reduce deaths of pregnant women by 15-50% and the deaths of their unborn children by 45-75%.

Pregnant women have a higher risk of dying if they experience any of three delays in accessing this care when they need it. These include a delay in deciding to seek care, a delay travelling to appropriate health facilities, or a delay in receiving the care they need when they get there.

In Nigeria, it’s the delay in travelling to receive care that is often the most deadly, with many women left to travel to health facilities either on their own or with support of their relatives, without professional help. This journey is thought of as a black box

because unravelling what happened during their travel, including delays experienced while en route, can only be analysed after it is already too late.

The promise of Google Maps

What if we could use Google Maps, the most popular navigation app on earth, to help understand these delays? In a recently published study, my colleagues and I assessed travel time to care for pregnant women in emergency situations using data from Google Maps.

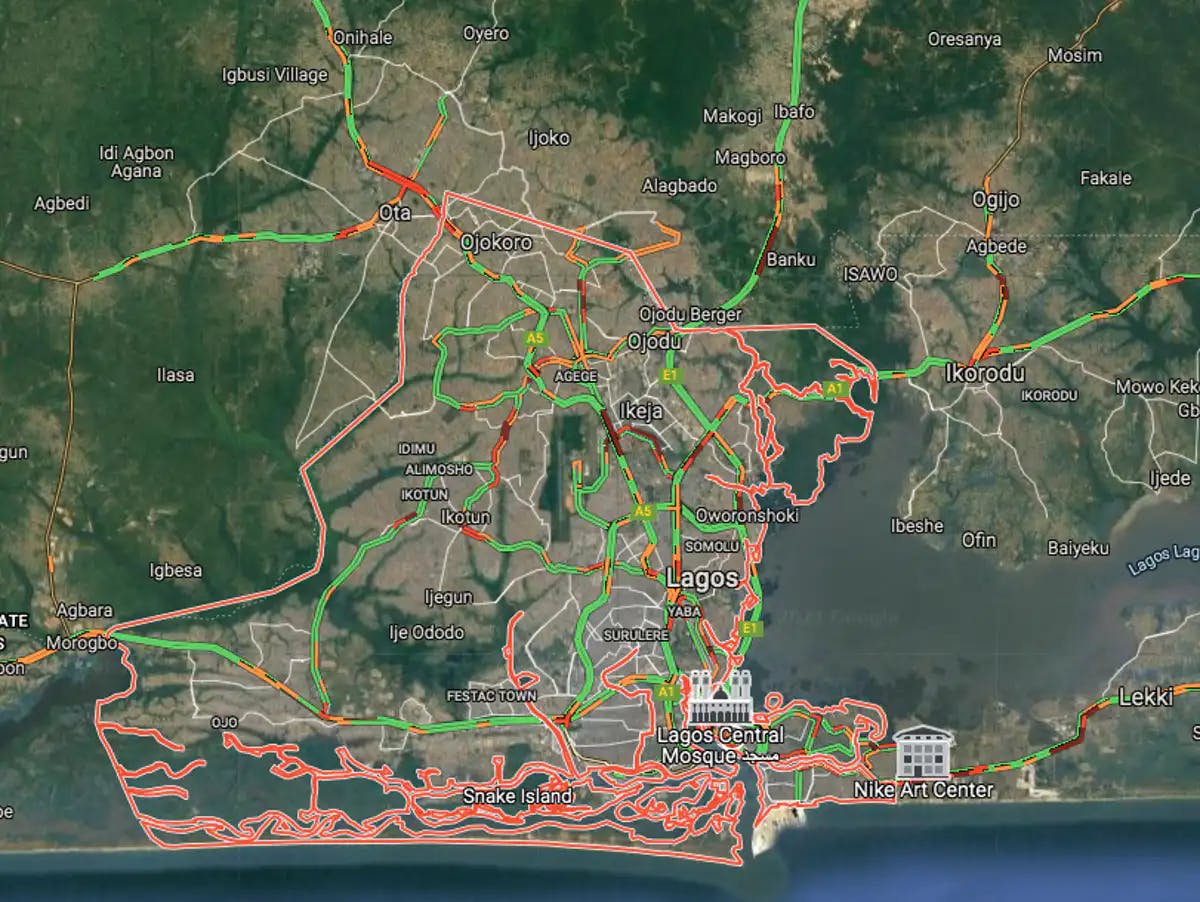

We used the travel time estimates we found to assess the coverage of critical maternity services in Nigeria’s most urbanised state and the largest city in sub-Saharan Africa – Lagos.

Google Maps data can help us understand pregnant women’s journeys to hospital for emergency care. Photo by: Google Maps

Our results showed that for women who travelled directly to a hospital, travel time ranged from 2 to 240 minutes. For those who went there after a referral, travel time ranged from 7 to 320 minutes. Total travel time was within 60 minutes for 80% of pregnant women. The time of day and having been referred were both associated with travelling more than 60 minutes.

We identified three hotspots from which pregnant women travelled more than 60 minutes to public hospitals in Lagos. These areas were Alimosho/Ifako-Ijaiye, Eti-Osa and Ijanikin/Morogbo. In cases when a referral was required, we identified a fourth hotspot in the north of Ikorodu, where pregnant women required more than 60 minutes to arrive at a hospital that could provide the care they need.

Eliminating hotspots

Our findings indicate that these hotspots require government intervention to reduce delays in women accessing care. The Lagos state government already appears to be addressing one of these hotspots by building the Eti-Osa Maternal and Child Care Centre.

Similar action is needed to address the Ijanikin/Morogbo hotspot, as there is currently no public hospital for about 30 km to the east and west of this cluster.

A healthy birth often relies on avoiding deadly delays in pregnant women accessing care. Photo by: Oni Abimbola/Shutterstock

For Alimosho/Ifako-Ijaiye and north of Ikorodu, there are established public hospitals within these areas already and it appears the challenge might be their relative inaccessibility. In these areas, road expansion and repair and the improvement of referral systems could be effective ways to minimize travel time.

Our research reinforces existing evidence that pregnant women face significant challenges in accessing emergency care. Even in places that are expected to have the so called urban advantage

, pregnant women in urgent situations still have to face traffic congestion, poor roads and slow referral systems.

For a pregnant woman in an emergency situation, delay can be a matter of life and death. If we are going to make progress in reducing maternal mortality, targeted actions that respond to local area-specific challenges like those recommended in our study will go a long way.